Overview

Folks that are involved in alliances and alliance management know well the challenges of making alliances work. Indeed, they spend significant time working to ensure that the key capabilities necessary to enhance the likelihood of alliance success are in place. That said, an underexplored area is that of alliance leadership and, in particular, the way in which the basic mechanism for alliance management — governance —fails to provide alliances some of what they need most — leadership. In this article we share some of our thinking about alliance needs, how more pro-active alliance leadership could help meet those needs, the ways in which alliance governance fails to provide that, and steps that organizations can take to ensure that appropriate alliance leadership is indeed in place.

The Sub-Optimizing Alliance: Classic Symptoms and a Picture of a Preferred Situation

In almost all instances in which we are asked to intervene in challenging or sub-optimizing alliances, we see many of the same symptoms. These include:

- Decisions that linger, that are made reactively, or are revisited after a seemingly final decision has been made

- Problems that are regularly escalated unilaterally within the chain of command of the separate companies, or that fester for too long without resolution

- Alliance members walking around with unanswered questions about the ultimate goals of and plans for the alliance, or with questions or concerns about the motives of the other side (e.g., “they are trying to get a better deal for themselves” or “they just don’t care as much as we do”)

- Folks feeling like there are all sorts of barriers in the way of their getting things done, be it the incentives of the other side, the fact that various processes, preferences and goals are not aligned, or a lack of a true meta purpose that is used by all involved to honestly and fairly arbitrate differences and work out issues

On an alliance where performance is optimized the picture would of course be very different —

- Decisions would be made, made efficiently, and in a way that maximized the likelihood of that decision’s effective implementation

- Problems would be solved at the lowest possible level and, when folks in different organizations ran into problems getting their issues resolved, would escalate those issues together, in a joint problem solving mode

- Alliance members would exhibit a high degree of trust in the other side — be it trust related to the other’s side strategic goals and the extent to which those goals are aligned with those of the alliance, the ability of the other side to operationally deliver on their commitments, or in the personal integrity of those with whom they work

- Partners would understand and seek to pro-actively lever-age each other’s strengths

- Folks up and down the alliance interface would use medium and longer term goals to guide decisions

- Governance teams would pro-actively and explicitly talk about and manage the tension between parochial and joint goals

- Communication channels would be strong, clear and used often/appropriately

Ultimately, the alliance would be functioning in much the same way as we all hope our individual companies would function — with clear goals, with folks collaboratively managing cross-organizational tensions, with exemplary execution based on alignment of goals where possible and mechanisms in place to manage differences where needed, and where all would be working under a truly facilitative common set of behavioral norms and expectations. Unfortunately, far too few alliances meet this picture of a preferred situation. As we explain below, in our experience a major reason why this is so is the way in which many companies set up alliance governance — indeed, at the end of the day alliance governance often fails to focus at all on filling the gap between the above described symptoms and the preferred situation.

Governance: It’s Not Leadership

There are of course many factors that contribute to an alliance not being as effective or profitable as the partners originally hoped. Some of these are out of the control of the people at any level of the alliance. However, in our experience, one of the most fundamental and in fact under-considered diagnoses for the problems alliances experience is the way in which organizations look to oversee the relationship — by putting in place alliance governance and not on alliance leadership. Strong leadership is fundamental to any company. Indeed, given that alliances tend to be extraordinarily complex to manage — to make them work organizations need to regularly overcome significant organizational difference (e.g., differences in planning processes, appetite for risk, importance of alliance in respective portfolios) — it is hard to see how leadership on an alliance could be less critical than that necessary to make individual companies work.

Truly effective leadership on an alliance serves the very same purpose that leaders serve as they lead within their own companies. Strong leadership — both in a company and on alliance — is an enabler of success. Thus, for example, strong leaders:

- Create a clear, compelling vision — one that connects to the individuals involved in personally meaningful enough ways to provide them the drive to do what needs to be done

- Focus in on the culture of the enterprise — thinking about what kind of culture do we want and how will that culture reflect our core values and ultimately lead to success. Based on that they then devise and implement multi-faceted plans to drive that view into the day to day behaviors of those involved and regularly monitor and change those plans to ensure optimal results

- Demand and model effective collaboration (where it is deemed necessary) and ensure that their people are supported in their efforts to do such

- Identify and root out roadblocks to folks getting things done, particularly when those roadblocks are cross-organizational

- Do not undermine leadership group decisions by talking to their direct reports about why they believe the decision was a bad one or by pointing out the ways in which the plan does not meet their group’s partisan interests

- Work with other leaders to agree a strategy and communicate, communicate, communicate.

Absent this kind of strong leadership, any organization’s success — and certainly an alliance’s — is seriously handicapped. Said another way, would any of us want to work in a company that had governance only — not leadership? The fact, however, is that many alliances do in fact have governance only. And, at the end of the day, for most organizations, alliance governance is reactive, and focused on after the fact dispute resolution or the monitoring of results. It is also often partisan — about protecting one or the other of the partners’ parochial interests rather than jointly leading (or even governing) the potentially value creating enterprise to great results.

Governance as Leadership: How to Make It Happen

Companies that wish to shift from an alliance governance approach to an alliance leadership one need to take several steps. First, key folks need to engage in a serious conversation about the differences between the two and the extent to which they are truly willing to embrace the changes necessary. Absent a serious commitment to alliance leadership as a fundamental enabler of an alliance dependent strategy the change simply will not happen. Once that commitment is in place, organizations then need to take a hard look at the basic alliance related business processes, roles, incentives and expectations of those involved in alliance governance/leadership. This will tend to lead to some important changes. These include:

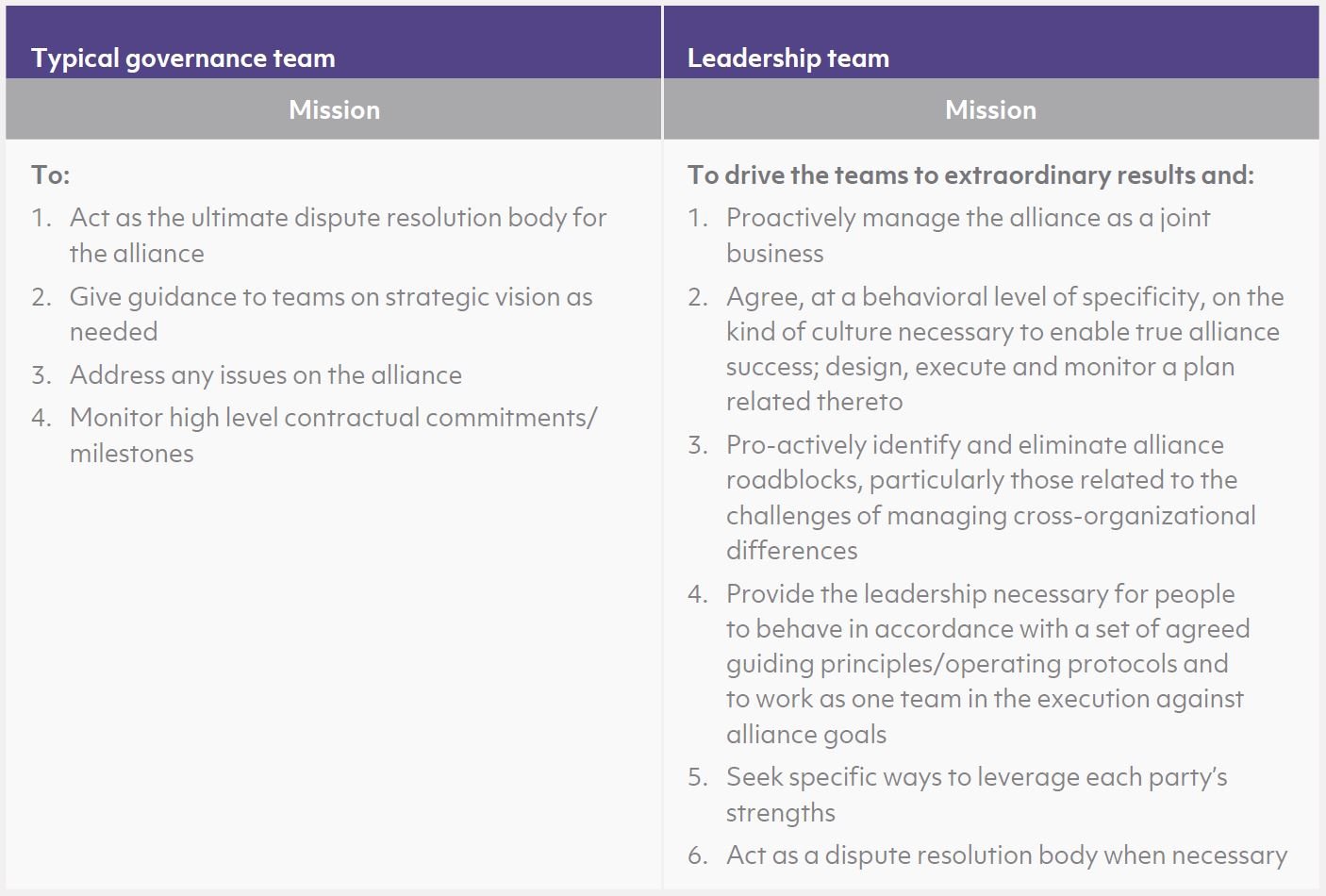

- During contract negotiations, companies need to talk explicitly with potential partners about the differences between governance and leadership and then, if appropriate to structure/mission a true leadership team (see sidebar for an example of the difference between those missions).

- Ensure that the right people — people who can in fact actually lead and with credibility in the organization — are placed on the leadership team. As part of that, organizations needs to make sure that the people they place as leaders on the alliance have sufficient time to devote to leadership activities and that their responsibilities as leaders of the alliance are not simply additional to their regular responsibilities, Far too often folks are placed on governance teams as an afterthought, without any consideration at all about what that will involve and the extent to which they have the time. The move from governance to leadership makes the importance of avoiding this situation even more pronounced.

- Judging alliance leaders in performance reviews on their leadership activities and on the success of the alliance, so that they are truly incented to play the role and put in the necessary time.

- Finally, as part of their standard alliance launch process, members of the new alliance leadership team need to take the time to discuss their role as leaders of the joint effort, thinking together about both (1) how, to meet this leadership view, they need to interact with one another and, as importantly, (2) how do they as a group need to interact with and be seen by those who report to them and/or are responsible for the day to day workings of the alliance. They also need to then create and implement their alliance leadership plan, essential-ly agreeing on how they will create and drive a vision, a culture, the basic working together assumptions of the alliance, and the like.

Conclusion

As alliances face the inherent challenges of working across two different, distinct organizations, leadership is fundamental to success. Organizations do their alliances a disservice by not putting in place individuals who are equipped to truly lead and are clear on what the role entails. Getting that kind of leadership, however, does not just happen. Alliancing organizations need to get clear about and committed to strong, active alliance leadership. With that, one of the key enablers of alliance success will be in place.

Illustration of Difference between Governance and Leadership Missions

Organizations typically create an alliance governance team, not leadership ones. Companies should consider making an active commitment to and planning for leadership on an alliance. A comparison of two team missions below helps illustrate the difference.

.png?width=512&height=130&name=vantage-logo(2).png)