Value-based or pay-for-performance approaches to reimbursement for drugs and devices represent a significant opportunity for innovation—but one that is often missed or misperceived by manufacturers and payers. This article takes a closer look at the current use of value-based agreements, how strategy informs their focus and development, and the very different set of skills it takes to prepare for and negotiate value-based agreements that actually create significant value for key stakeholders—including, most importantly, patients seeking access to new and often high-cost therapies.

The healthcare industry is abuzz with talk of value-based agreements—also called outcomes-based, risk-sharing, or pay-for-performance contracts. “Value-Based Arrangements May Be More Prevalent than Assumed,” reports a team of researchers writing in the American Journal of Managed Care.

Reflecting a broader trend of interest in alternative healthcare payment models, VBAs in part are a response to the political hot button of drug pricing—and also to patients’ and their advocates’ demands for access to novel, sometimes extraordinarily expensive therapies. Instead of paying a single negotiated price for a pharmaceutical therapy or medical device, VBAs tie reimbursement for prescriptions to their actual efficacy for patients.

Though data is limited, research suggests that 75% of VBAs are not publicly reported. Agreements that are publicly reported vary in their approach and ambition. For example:

- UPMC and Harvard Pilgrim have forged several outcomes-based arrangements with drug makers. In January 2019, UPMC Health Plan and AstraZeneca announced a VBA for Brilinta (ticagrelor), a blood thinner for cardiac patients; Brilinta is available in UPMC’s generic tier with payment tied to reduced incidence of hospitalization post-heart attack. UPMC negotiated to tie the price of Boehringer Ingelheim’s Jardiance to total care costs for all UPMC type 2 diabetes patients.

- For Spark’s Luxterna, a novel gene therapy for the treatment of congenital vision loss, Harvard Pilgrim links payment to both 90-day and 30-month efficacy.

- Novartis’s Kymriah and Kite’s Yescarta are chimeric antigen receptor (CAR-T cell) therapies—FDA-approved for some non-Hodgkin lymphoma and leukemia patients, and in trials for other forms of blood cancer. Priced in the hundreds of thousands of dollars range, they include rebates and discounts tied to performance.

- Novartis launched its multi-million-dollar one-time therapy Zolgensma with an installment payment plan, discounts for standard terms, and a money-back guarantee.

Yet despite these and other prominent examples—and despite indications of a recent uptick in the number of agreements, both reported and unreported—VBA utilization remains limited, and many VBAs actually deliver limited value.

Certainly there are good reasons for why pharmaceutical companies and healthcare payers should proceed carefully and selectively with value-based pharmaceutical contracts. In some cases, enthusiasm for VBAs can be little more than a new approach for payers to seek a discount; in these sorts of contract negotiations, “innovation” is the code word for “we want to pay less.” How might a manufacturer respond? We suggest testing some value-based models that are demonstrably focused on outcomes. If the therapy delivers the results and the payer still wants to pay less, then discount is the goal; if the payer is willing to pay above list price when the therapy delivers exceptional value, the goal is enhanced patient outcomes. (See more on negotiation below.)

Other VBAs barely stick a toe into the waters of alternative payment models—for example, offering rebates or discounts that tweak pricing by a few percentage points rather than meaningfully linking payment to outcomes. Such VBAs are likely to offer little actual value—and therefore seem hardly worth the significant effort it takes to negotiate and execute them successfully.

Value-Based Agreements: Theory versus Real World

VBAs vary widely in complexity, and many agreement structures are much harder to actually implement than traditional contracting arrangements. Typical pharmaceutical therapies and medical devices are sold as products that sit in a formulary or inventory; eventually they are used, and whether they work or don’t work, the drug or device maker is paid. Pricing is generally based on clinical trial data and economic modeling of the costs the therapy would reduce—if it works—modified by competitive pressures. In theory, VBAs rationalize pricing by tying reimbursement more directly to actual patient results, improving the basis for value exchange by better aligning incentives between manufacturers and payers. In theory.

In the real world, there are many questions and challenges in negotiating, implementing, and tracking value-based agreements. Data for actual outcomes can be hard to come by, and even when outcomes are tracked, it’s difficult to account for other factors that influence treatment efficacy and patient outcomes. Moreover, payers often are less focused on specific treatment outcomes than on reducing overall medical expenses over time. For most if not all payers, another barrier to VBAs can be the systems that support reimbursement—which are built on the implied model that you pay on day one for a therapy and are done with that transaction. All the relevant systems—from authorization to reimbursement to payment to security—are designed to support one-time payments. So you can imagine the accounting problems that ensue the first time a payer reimburses only half the price of the therapy on day one, then makes additional payments at, say, quarterly milestones to line up with measured outcomes.

For these reasons, it makes little sense to do a value-based agreement just to say you’ve done a value-based agreement. So, when can you create sufficient value for VBAs to make sense—and how should they be approached?

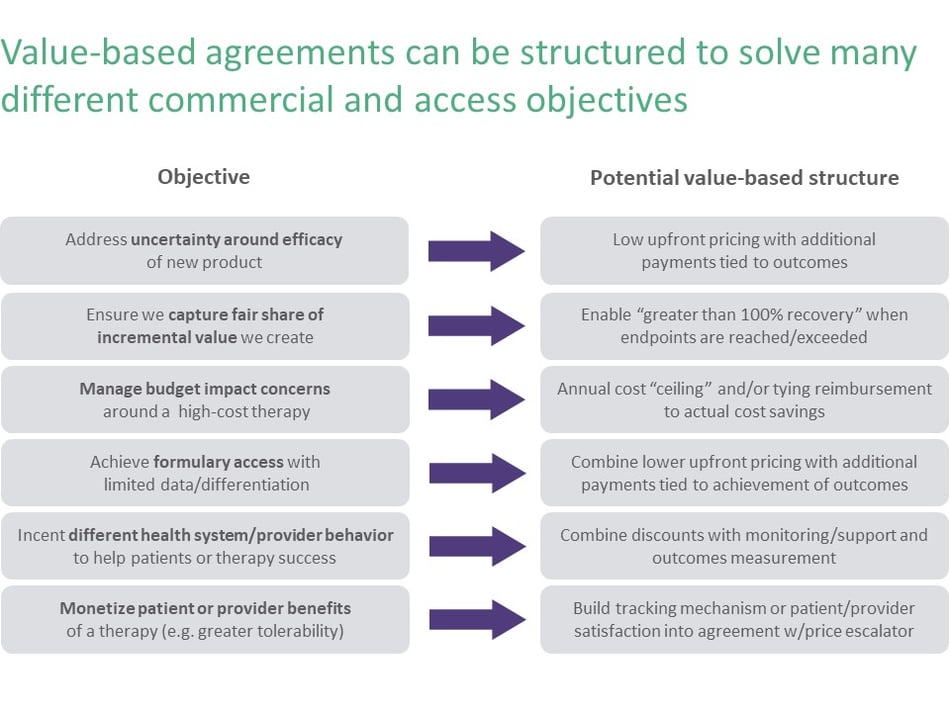

Value-based agreements need to fit into your organization’s overall strategy and context—and should only be pursued when they have potential to add significant value. The starting point for using a VBA for any product should be getting clear on the specific problem you are seeking to solve through a VBA, as Figure 1 emphasizes. For instance, you might seek a VBA because you believe your product’s actual efficacy will be more compelling to the payer than your current clinical trial data. In this instance, a VBA allows you to benefit from the actual impact of your products before you get the data that justifies higher pricing. You also might negotiate a VBA because your payer appears genuinely interested in innovating and is pushing you to think about different models in a therapy area where you see opportunity or have a strong pipeline. Or, perhaps your product is later to the market and lacks significant clinical differentiation. Instead of giving a big discount just to get on formulary, you might construct a VBA with a lower initial price to get access and give you some degree of upside if your therapy performs well.

The most innovative use of VBAs involves not just contracting around a therapy, but instead using the VBA to create additional value through delivery of an overall solution. For example, you might combine a therapy with coaching and a mobile app that together address a patient’s underlying unmet need and track results—and then, via the VBA, share in the benefit that is generated when you impact the clinical problem in a holistic way. Building a broad solution, and ensuring fair return on investment through a VBA, can provide a powerful approach to complex patient challenges while also managing the measurement challenge many VBAs face.

The Negotiation Mindset and Process (Hint: It’s Not Selling)

Value-based agreements require a different mindset and process than typical “customer-supplier” negotiations. Executing a value-based agreement requires extra steps and much broader stakeholder engagement. You can’t just negotiate price and sell; instead, you need to uncover interests and build alignment around a shared desire to create value, versus just focusing on distributing value. Similarly, the parties need to accept joint risk rather than endeavoring to shift risk to the other party. Details such as measurement and tracking must be assessed and jointly agreed. Value-based agreements require a long view of value, too—emphasizing successful implementation over time instead of seeking just to “close the deal.”

Internally, before sitting down with the payer to negotiate, manufacturers need to spend considerably more time assessing therapy benefits and modeling the risk they take with different types of value-based models. Will we do better (for ourselves, for patients, for payers or providers) utilizing a VBA or a traditional reimbursement mechanism? Do the upside and the value created justify the investment and additional complexity? Payers similarly need to develop their own value-based models—and determine if their systems can accommodate therapies whose price might be different on day 180 than on day one.

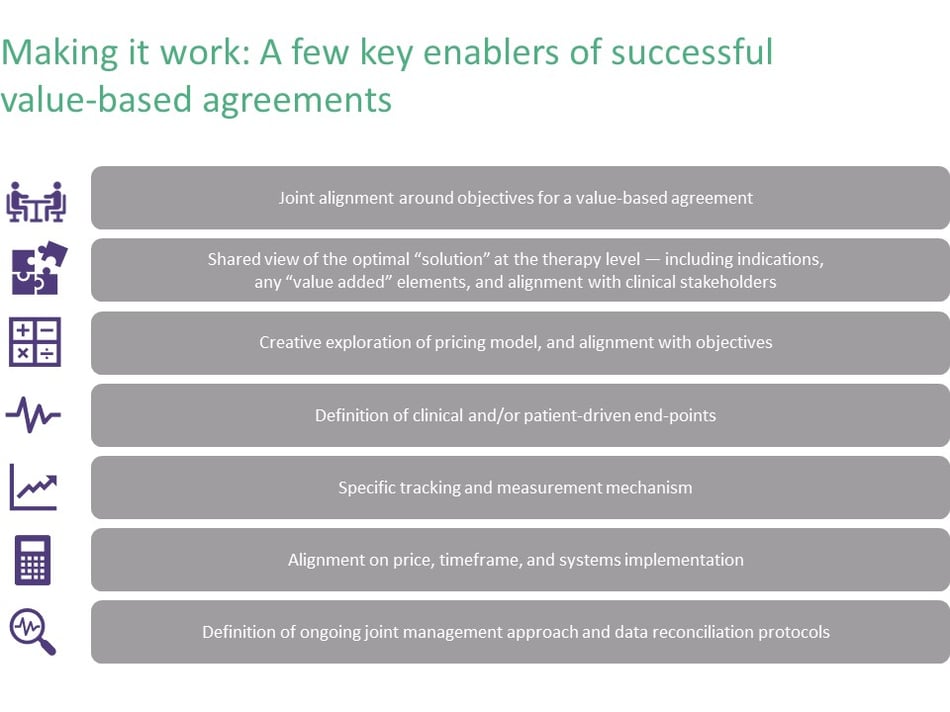

Forging a value-based agreement involves preparing for something very different than typical pharmaceutical sales negotiation. Keys to successful negotiation include more analysis, a flexible and iterative engagement approach, and a fuller understanding of what the value proposition is for both sides and how each side’s interests will be met. It requires different skills to surface and explore these interests early in the process, and to jointly design a solution that meets these interests. Successful VBA negotiations require building broad internal alignment within the manufacturer (across product teams, finance, compliance, pricing, and contracting) as well as alignment with external stakeholders within payer organizations and often provider and patient groups as well.

Value-based agreements—designed and executed well—represent an opportunity to more artfully meet the interests of different stakeholders in the healthcare ecosystem, as shown in Figure 3. Ideally, manufacturers end up providing more value to patients, providers, and payers while creating a different kind of working relationship with the payer they’re reaching an agreement with—not only understanding different stakeholders and what each one cares about, but also gleaning much deeper insight into how the payer and the patient are experiencing the disease. Because VBAs require tracking of outcomes, they can generate highly valuable (and otherwise costly to acquire) real world evidence and provide a better grasp of the full patient journey. VBAs also provide an opportunity for therapies to maximize their value for the manufacturer—which requires selecting the right structure of value-based agreement based on market strategy and product differentiation.

Assessing when to pursue value-based agreements, and how, is essential to getting your product strategy right. Approached strategically and implemented effectively, VBAs can enhance your understanding of the key stakeholders you engage with. They also can inform the capabilities you need to implement VBAs that actually deliver value.

For more on our experience in this area, visit our Market Access page.

Our full array of Life Sciences expertise can be viewed here.

.png?width=512&height=130&name=vantage-logo(2).png)