We have all heard it — the structure of today’s organizations drives the need for influence to be developed as a core competency across all levels and roles. Enterprise-wide initiatives and matrixed reporting lines means more of us are increasingly dependent on the cooperation of others, over whom we have no formal authority, to complete tasks and achieve our goals.

However, knowing that the ability to influence others is the way through the sticky web of a complex business environment is one thing, being successful at it is quite another. Common influence strategies and tactics often prove inadequate:

- Approaching influence as something that is done to others, and not a collaborative activity to be engaged in with others

- Creating conversations that allow for only two responses — agree or disagree

- Focusing only on attractive ways of presenting our own ideas without doing enough to understand resistance of others

- Using organizational hierarchy to determine who is the decision maker

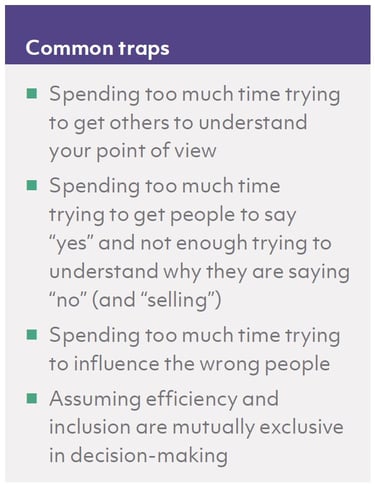

So this is our challenge — when important outcomes are at risk, when we are confronted with a complex landscape of stakeholders with conflicting interests, and when we need to influence others with whom we will have ongoing inter-actions, and thus need to build strong working relationships, how do we avoid common influence traps?

Trap 1: Spending too much time trying to get others to understand your point of view

Many people fail to be persuasive because they naturally assume that influencing someone is short-hand for getting that person to agree with them. This mindset of “I have the right answer, and my job is to get you to agree,” is very risky. It often results in the other person (or people) feeling disrespected and pressured. Ironically, we are least persuasive when we are most forcefully defending our own views and putting down or minimizing the views of others.

So how do you avoid falling into this trap? The first step is recognize how much time and effort (and PowerPoint decks) we put into advocating our point of view or preferred solution when there is no way we can have absolutely all the information. When (if) we stop to ask a question, the questions are typically used to poke holes in the other person’s arguments. The jaws of the bear trap opens when we fall into a pattern of defending our views or solutions, and snap shut as we fail to expend any effort trying to understand, much less learn from, other perspectives. Being persuasive in the face of disagreement requires us to let go of the urge to fight for our view. We need to be willing to share our entire chain of reasoning (the facts we are considering, our assumptions, and the conclusions we are making) and invite comment, challenge and alter-native views. In doing so, we are much more likely to create a conversation where the other person feels welcomed to listen to our views and share theirs. Rather than look for opportunities to tell the other person why they are wrong, ask questions that are based on genuine curiosity about how and why someone may see a situation very differently than we do. To be persuasive, it is essential that we remain open to persuasion our-selves. After all, when was the last time someone convinced you by forcefully pushing their view and being unwilling to listen to your perspective?

Trap 2: Spending too much time trying to get people to say “yes” and not enough time trying to understand why they are saying “no”

When faced with disagreement, we often spend an inordinate amount of time coming up with all the reason why the other person should say yes, or why it would be foolish for them to say no. Sometimes this works, but often, especially when the stakes are high, the other person just digs in their heels. This continued resistance to what we believe is the best course of action, may lead us to think the other person is irrational, ill informed or just plain difficult. It is a natural tendency in the face of resistance to push harder. However, the unfortunate and unintended con-sequences more often than not are that the person simply feels unheard and/or they respond with stronger (more vehement) objections -now thinking that we are the irrational, ill-informed, or just plain difficult person.

To avoid this trap, we need to step into the other person’s shoes. They are saying no to us because to them, that is the right answer — people do what they see in their best interest. We need to find out why they see “no” as being in their best interest. An easy, back-of-the-envelope way to do this is to systematically think about all the possible reasons, from the other person’s perspective, why saying “no” seems to be reasonable. The discipline of trying to understand resistance as founded in potentially reasonable concerns or as a symptom of unmet needs provides important and helpful information that can move us away from a fruitless battle of wills to a place of collaboration. Once we understand, from their perspective, why they are resistant, we can then put forward a proposal, suggestion, etc. in a way that demonstrates a respect for their interests. Thus, leading to a greater chance of buy-in.

Trap 3: Spending too much time trying to influence the wrong people

Even in highly matrixed organizations, we often bring the mindset of a hierarchical organization to our thinking — the most senior person is the one, and perhaps even the only, person we need to get buy-in from. In reality, the person (or people) who is the decision maker or has “power” connected to the situation might be a peer or even a direct report. Many people think about their stakeholders, and may even list them out; however, rarely do they systematically map out and think systematically through the web of interconnected relationships among various stakeholders based on the specific situation at hand (e.g. proposal you are trying to get alignment around).

Consider using the following steps to create a mind map of the stakeholders: 1) list your stakeholders and draw them out in a map; 2) analyze the level of power and authority of each party with respect to their ability to approve and/or implement your proposal or request; 3) analyze each party’s disposition with respect to your request or proposal; 4) analyze relationships of deference, influence, and antagonism among stakeholders. This map should help you clarify whom to approach and in what sequence, and how to leverage strong relationships and stakeholder support to constructively address opposition. Keep in mind that engagement with individual stakeholders may comprise a range of different conversations, from direct efforts to persuade, to requests for assistance engaging or persuading other stakeholders, to consultation and requests for input, to simply getting to know key stakeholders and beginning to build relationships. As you develop your mind map, use the evolving picture to help you think through what you know about each person, what additional information you need to gather, and how you might do so.

Trap 4: Assuming efficiency and inclusion are mutually exclusive in decision making

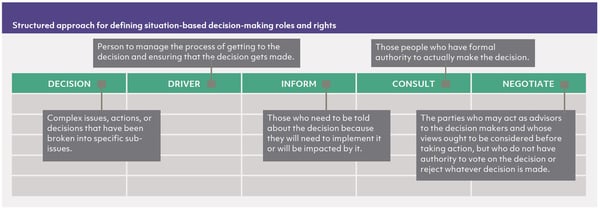

A very common trap in complex, matrixed organizations when it comes to decision making is failing to include all the necessary stakeholders, or swinging the pendulum too far in the other direction, and including everyone. Including too many people leads to delays in action but an insufficiently inclusive process risks overlooking important information or perspectives. To further complicate the landscape, soliciting information can feel risky because it often creates an expectation that advice or suggestions will be followed. This risk must then be balanced with the risk that an insufficiently inclusive process may lead those who feel excluded to resist implementing decisions. When the ultimate decision maker(s), or appropriate level of inclusiveness, is unclear it can make creating a successful influence strategy difficult at best and create decision making paralysis at worst.

To avoid this trap, consider that different people have different interests and should have different roles in making decisions. Identifying the high impact, vital few areas and clarifying decision roles and rights that impact them are key to execution effectiveness. It is helpful to set expectations about who will be involved in what ways in various types of decision making and how to work through complex decisions. Consider using a structured approach, like the matrix above, for defining situation-based decision making roles and rights.

Conclusion

Identifying and avoiding these traps may seem simple, and to a large degree they are. Nonetheless, when things get busy and important decisions are on the line, ingrained habits tend to surface when they are least helpful. Enhancing our ability to influence others depends in large part on changing deeply engrained assumptions about influence, and beginning to view ourselves, and others, in a new and different light. Investing time in shifting your thinking to influence as a collaborative activity will guide your behavior to more powerful and productive patterns leading to the results you want and need.

.png?width=512&height=130&name=vantage-logo(2).png)